Scientists Discover the First Virus-Eating Organism

(Image: Konstantin Kolosov/Pixabay)The so-called “circle of life” dictates that if a living thing exists, it’s probably food for something else. Viruses, however, have historically managed to escape this unofficial rule. Although plenty of organisms eat viruses accidentally as they consume other living things, no organism has been known to munch viruses on purpose—until now.

A research team at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has identified the first known “virovore,” or virus-eating organism. Biologist John DeLong was leading his colleagues in the search for virus-consuming microbes by taking freshwater samples from a nearby pond. Back at the lab, the team isolated the samples’ various microbes and added chlorovirus—an algae-targeting freshwater virus—to the water. Eventually, they found exactly what they were looking for: a ciliate (or single-celled organism with hair-like cilia) referred to as Halteria.

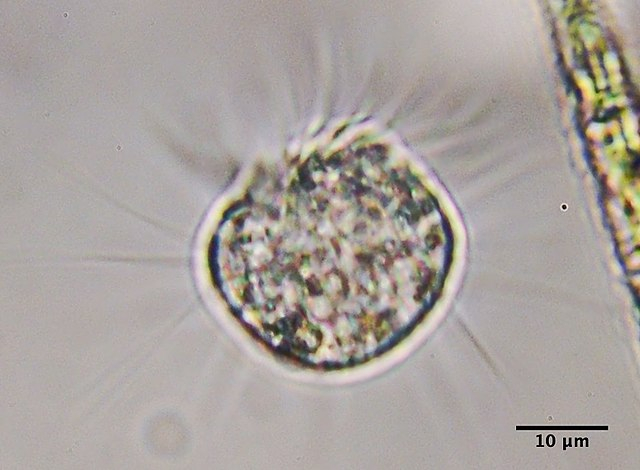

Halteria under a microscope. (Image: Don Loarie/Wikimedia Commons)

Scientists have known about Halteria’s existence for quite some time, but they’ve always thought the ciliate consumed only bacteria. But in the lab, Halteria showed an appetite for far more than their typical algae: They appeared to be devouring the added chlorovirus. When DeLong’s team eliminated all food sources other than chlorovirus from their sample tanks, Halteria grew 15-fold in just two days. Meanwhile, chlorovirus levels dropped to just 1% of its original population.

DeLong and his team sought to confirm Halteria’s appetite for chlorovirus by injecting the virus with fluorescent dye. Soon enough, Halteria began to glow. The team also saw that Paramecium bursaria, another freshwater-dwelling ciliate, appeared to consume chlorovirus; however, Paramecium didn’t grow in size or population after doing so.

Viruses are abundant in water and are chock-full of “raw materials” like nitrogen, phosphorus, and nucleic acids, making them a convenient snack for organisms willing to chow down on them. DeLong’s team believes the discovery of Halteria’s intentional virus consumption could guide broader ecological studies, such as those involving aquatic food webs. As they note in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, current food web models neglect the interactions between viruses and their predators; research like DeLong’s might inform the expansion of those webs to include the consumption of viruses.

Now Read:

Comments are closed.