Scientists Develop Tiny Implant That Helps Fight Cancer

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a T cell. (Image: NIAID/Wikimedia Commons)A new implant could become a key tool in the fight against various forms of cancer. Researchers in California have developed a tiny device designed to be placed directly next to a tumor within the body. Once implanted, the device helps to shrink the existing tumor while preventing new ones from forming.

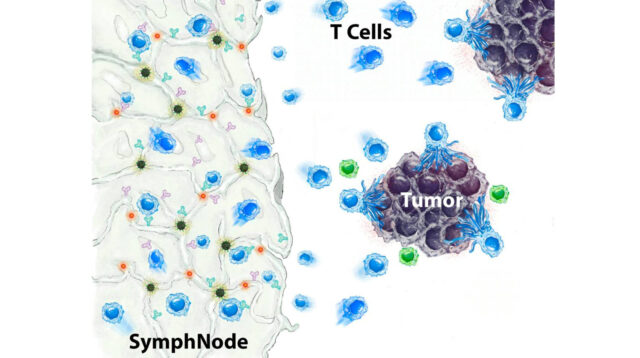

The implant, called SymphNode, is the latest creation out of an interdisciplinary research lab at the University of California, LA (UCLA). At first glance, SymphNode—named after its resemblance to the lymph node—looks like a tiny sponge about the size of a pencil eraser. But inside the body, it’s much more than that. The device is made of alginate, a brown algae byproduct used in food manufacturing and dental impressions that also serves as a fantastic catalyst for gradual drug release. Once implanted, SymphNode begins to deliver a small-molecule tumor growth inhibitor that suppresses regulatory T cells (Treg), which are known to encourage tumor development.

That’s only one of the SymphNode’s functions. The device simultaneously uses chemokines, a type of protein, to attract effector T cells, which coordinate and help carry out the body’s immune response. Newly-recruited effector T cells find a home within SymphNode, using the pores in the spongy device to enhance their own performance.

(Image: Negin Majedi/Symphony Biosciences)

In a paper for the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering, the researchers describe testing SymphNode in mice with breast cancer and/or melanoma. Of the mice with breast cancer, 80% experienced a reduction in tumor size; of those with melanoma, 100% of tumors shrank. Cancer stopped spreading in 100% of mice with breast cancer while spread only stopped in 40% of those with melanoma. All treated mice experienced a significant lifespan compared with control mice, some of which died in half the time as their cancers metastasized.

Best of all, treated mice who’d survived cancer using SymphNode also survived a second tumor that was injected 100 days later. The team at UCLA believes this is because memory T cells (which stick around long after the initial threat has passed) “remembered” how to eliminate cancer cells following their initial experience.

The researchers plan on figuring out SymphNode’s efficacy in humans via Symphony Biosciences, a startup they founded on UCLA’s campus. Meanwhile, they’re working on creating an even smaller, injectable version of SymphNode that would preclude surgical implantation.

Now Read:

Comments are closed.